The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a way that federal and state governments help working people with lower incomes. Most analysis of how the EITC works looks at its economic effects.

Researchers funded by NIMHD are exploring a different kind of effect: whether economic assistance improves health—specifically, whether it leads to healthier pregnancies. More money could mean better prenatal care, or healthier food.

The researchers have found that what lawmakers do is reflected in the bodies of their tiniest constituents: A series of studies on economic policy and births has found that more generous policies result in fewer babies with low birthweights.

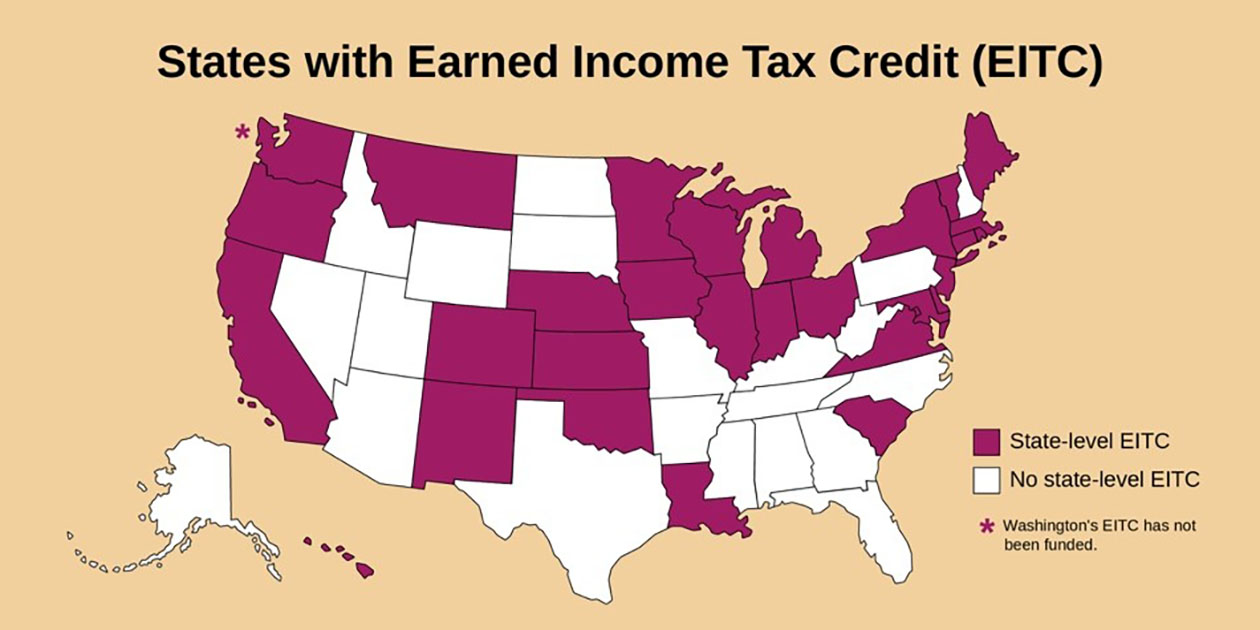

Different Policies in Different States

The federal government has offered an EITC since the 1970s. Some states began introducing their own EITCs in 1988. Today, about half of the states, as well as Washington, D.C., have an EITC, with most set as a percentage of the federal EITC.

Studies have shown that the federal EITC has reduced poverty and increased the number of people who work, since it is available only to people who earn money. “There’s evidence that it’s one of the most effective anti-poverty programs for families in the U.S.,” says Kelli Komro, Ph.D., M.P.H., a public health researcher at Emory University in Atlanta who has funding from NIMHD to study the effects of public policy on children’s health.

Komro wanted to know how the EITC affects health. “We have all of these natural experiments occurring at the state level,” she says. By comparing states with different policies and over time, Komro and her colleagues hoped to learn about the policies’ implications for family health.

Investigating Health Effects

The research team focused on babies. “We look at birth outcomes because they are sensitive to poverty and a family’s economic status,” Komro says. “Birth outcomes” include whether babies are born at a low weight (less than 5.5 pounds) and whether they are premature. Premature and low-birthweight babies are more likely to have health problems at birth and later in life. Many factors contribute to the link between poverty and birth outcomes. Economically disadvantaged mothers may not have access to good prenatal care; they also may not be able to get enough healthy food. Studies have also found that many people living in poverty have high stress levels, which can affect a growing fetus.

Komro and her colleagues worked with a team of legal researchers to classify the laws by how generous they were. Because they do not know exactly which mothers received the EITC, the researchers could not directly measure how the EITCs affected individual birthweights. The group focused on women with a high school education or less, because most EITC recipients have this level of education.

The researchers found that states with more generous EITCs had fewer babies born at a low weight—leading to several thousand fewer babies being born with a low weight each year.1 The most generous EITCs were even better for babies’ health. The researchers speculate that this could be because the EITC reduces stress. The tax credit may also make it possible for women to buy healthier food or afford better housing.

The researchers also examined the experience in Washington, D.C., which increased its EITC several times over an 8-year period, and found that the percentage of babies who were born underweight dropped every time the EITC increased.2

Komro and her colleagues also examined states’ data to find out whether EITCs helped mothers of different races and ethnicities. They found that rates of low birthweight fell for babies born to White, Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic mothers; the EITC seems to help everyone.3

Komro concludes that the EITC is “clearly helping families and improving the health of children.”

Applying the Findings

“It is impressive to see how this kind of policy change can affect babies”, says Jennifer Alvidrez, Ph.D., scientific program officer for Clinical and Health Services Research at NIMHD.

Researchers will need to continue to dig deeper to understand exactly how the EITC makes for healthier babies, Alvidrez says: “Is it about having more money to pay for prenatal care? Is it that you can go to the pediatrician more often? Is it just because you’re not so stressed out about money?” Once researchers understand how the process works, she says, it might be possible to find more targeted or more effective ways to help families.

Komro occasionally hears from people who want to understand how her research is relevant to their states. Her own state, Georgia, does not offer a state-level EITC. “There are groups in Georgia that are advocating for a state-level EITC,” Komro says. “Every legislative session in Georgia, they’re trying to move it forward. I believe it is important to inform the legislators about the scientific evidence of the health effects of such policies.”

A few years ago, Komro’s team found similar results for minimum wage laws. The federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour, but some states have set their minimum wages higher. In states with more generous minimum wage laws, fewer babies had low birthweights and fewer babies died between the ages of 1 month and 1 year. If every state had increased its minimum wage by a dollar in 2014, the researchers concluded, an estimated 518 fewer babies would have died between the ages of 1 month and 1 year.4

The researchers made their classification of minimum wage laws available through the website LawAtlas.org, so that others who would like to study the effects of minimum wage can start with the same dataset. They also plan to make the EITC data available.

Komro and her colleagues are also currently carrying out research on the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. The federal government gives block grants to states for TANF, and states choose how to carry out the program.

References

Posted June 1, 2020

More Information

Read more about this research in the .

Learn more about state earned income tax credits from this article by Dr. Komro and a colleague on the website Econofact.

Read how NIMHD-funded researchers have mapped neighborhood deprivation.